Condition Information

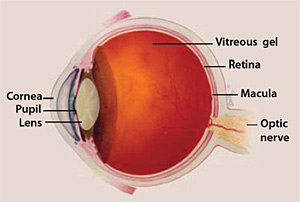

Macular edema is the build-up of fluid in the macula, an area in the center of the retina. The retina is the light-sensitive tissue at the back of the eye and the macula is the part of the retina responsible for sharp, straight-ahead vision. Fluid buildup causes the macula to swell and thicken, which distorts vision.

What causes macular edema?

Macular edema occurs when there is abnormal leakage and accumulation of fluid in the macula from damaged blood vessels in the nearby retina. A common cause of macular edema is diabetic retinopathy, a disease that can happen to people with diabetes. Macular edema can also occur after eye surgery, in association with age-related macular degeneration, or as a consequence of inflammatory diseases that affect the eye. Any disease that damages blood vessels in the retina can cause macular edema.

Structures of the Eye

What are the symptoms of macular edema?

The primary symptom of macular edema is blurry or wavy vision near or in the center of your field of vision. Colors might also appear washed out or faded. Most people with macular edema will have symptoms that range from slightly blurry vision to noticeable vision loss. If only one eye is affected, you may not notice your vision is blurry until the condition is well-advanced.

Diabetic macular edema (DME)

Diabetic macular edema (DME) is caused by a complication of diabetes called diabetic retinopathy. Diabetic retinopathy is the most common diabetic eye disease and the leading cause of irreversible blindness in working age Americans. Diabetic retinopathy usually affects both eyes.

Diabetic retinopathy is caused by ongoing damage to the small blood vessels of the retina. The leakage of fluid into the retina may lead to swelling of the surrounding tissue, including the macula.

DME is the most common cause of vision loss in people with diabetic retinopathy. Poor blood sugar control and additional medical conditions, such as high blood pressure, increase the risk of blindness for people with DME. DME can occur at any stage of diabetic retinopathy, although it is more likely to occur later as the disease goes on.

Experts estimate that approximately 7.7 million Americans have diabetic retinopathy and of those, about 750,000 also have DME. A recent study suggests that non-Hispanic African Americans are three times more likely to develop DME than non-Hispanic whites, most likely due to the higher incidence of diabetes in the African American population.

Eye surgery

Macular edema may develop after any type of surgery that is performed inside the eye, including surgery for cataract, glaucoma, or retinal disease. A small number of people who have cataract surgery (experts estimate only 1-3 percent) may develop macular edema within a few weeks after surgery. If one eye is affected, there is a 50 percent chance that the other eye will also be affected. Macular edema after eye surgery is usually mild, short-lasting, and responds well to eye drops that treat inflammation.

Age-related macular degeneration

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a disease characterized by deterioration or breakdown of the macula, which is responsible for sharp, central vision. In neovascular AMD, also called “wet” AMD, blood vessels begin to grow up from the choroid (the bed of blood vessels below the retina) and into the retina. These new and abnormal blood vessels leak fluid into the macula and cause macular edema.

Blockage of retinal blood vessels

When retinal veins are blocked (retinal vein occlusion), blood does not drain properly and it leaks into the retina. If it leaks into the macula, this produces macular edema. Leakage is worsened by the severity of the blockage, how many veins are involved, and the pressure inside them. Retinal vein occlusion is most often associated with age-related atherosclerosis, diabetes, high blood pressure, and eye conditions such as glaucoma or inflammation.

Inflammatory diseases that affect the retina

Uveitis describes a group of inflammatory diseases that cause swelling in the eye and destroy eye tissues. The term “uveitis” is used because the diseases most often affect a part of the eye called the uvea. However, uveitis is not limited to the uvea. Uveitis can affect the cornea, iris, lens, vitreous, retina, optic nerve, and the white of the eye (sclera).

Inflammatory diseases and disorders of the immune system may also affect the eye and cause swelling and breakdown of tissue in the macula. These disorders include cytomegalovirus infection, retinal necrosis, sarcoidosis, Behçet’s syndrome, toxoplasmosis, Eales’ disease, and Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome.

How is macular edema diagnosed?

To diagnose macular edema, your eye care professional will conduct a thorough eye exam and look for abnormalities in the retina. The following tests may be done to determine the location and extent of the disease:

Visual acuity test. A visual acuity test is a common way to identify vision loss and can help to diagnose vision loss as a result of macular edema. This test uses a standardized chart or card with rows of letters that decrease in size from top to bottom. Covering one eye, you will be asked to read out loud the smallest line of letters that you can see. When done, you will test the other eye.

Dilated eye exam. A dilated eye exam is used to more thoroughly examine the retina. It gives additional information about the condition of the macula and helps detect the presence of blood vessel leakage or cysts. Drops are placed in your eyes to widen, or dilate, your pupils. Your eye care professional then examines your retina for signs of damage or disease.

Fluorescein angiogram. If earlier tests indicate you could have macular edema, your eye care professional may perform a fluorescein angiogram. In this test, a special dye is injected into your arm and a camera takes photos of the retina as the dye travels through the blood vessels. This test helps your ophthalmologist identify the amount of damage to the macula.

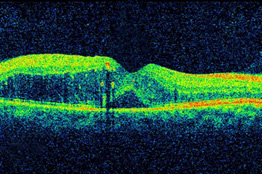

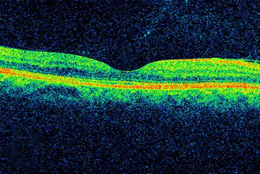

Optical coherence tomography. This is a test that uses a special light and a camera for detailed views of the cell layers inside the retina. It detects the thickness of the retina and so it’s useful in determining the amount of swelling in the macula. Your eye care professional may also use optical coherence tomography after your treatment to track how well you are healing.

The Amsler Grid. The Amsler Grid provides an easy way to test whether or not your central vision has changed. It can recognize even small changes in your vision.

If you need reading glasses, wear them when you look at the Amsler grid. The grid should be at the same distance from your eyes as your usual reading material – about 14 inches. Test both eyes, one at a time, to see if any parts of the grid look distorted, missing, or dark. Mark the areas of the chart that you’re not seeing properly and bring it with you to your next eye exam.

Treatment Information

DME, as viewed by optical coherence

tomography (OCT). The two images were

taken before (Top) and after anti-VEGF

treatment (Bottom). The dip in the retina

is the fovea, a region of the macula where

vision is normally at its sharpest. Note the

swelling of the macula and elevation of

the fovea before treatment.

Treatment for macular edema is determined by the type of macular edema you have. The most effective treatment strategies first aim at the underlying cause of macular edema, such as diabetes or high blood pressure, and then directly treat the damage in the retina.

Treatments for diabetic macular edema and macular edema caused by other conditions are often the same. However, some cases of macular edema may need additional treatments to address associated conditions.

In the recent past, the standard treatment for macular edema was focal laser photocoagulation, which uses the heat from a laser to seal leaking blood vessels in the retina. However, recent clinical trials, many of them supported by NEI, have led doctors to move away from laser therapy to drug treatments injected directly into the eye.

Anti-VEGF injections

The current standard of care for macular edema is intravitreal injection. During this painless procedure, numbing drops are applied to the eye, and a short thin needle is used to inject medication into the vitreous gel (the fluid in the center of the eye). The drugs used in this treatment –Avastin, Eylea, and Lucentis – block the activity of a substance called vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). VEGF promotes blood vessel growth. In a healthy eye, this is not a problem. But in some conditions, the retina becomes starved for blood and VEGF becomes overactive. This causes the growth of fragile blood vessels which can rupture and leak blood into the retina and macula, causing macular edema. Anti-VEGF treatment blocks the activity of VEGF and slows the progress of macular edema.

The anti-VEGF drugs all work in similar ways to block vessel formation and prevent leakage in the retina. A recent NEI-supported clinical trial that directly compared the effectiveness of the three drugs for DME found that the drugs performed similarly for patients with mild vision problems. However, Eylea performed better for those with more serious vision loss (20/50 or worse). Your eye care professional will discuss which drug treatment is the best option for you.

Anti-inflammatory treatments

Corticosteroid (steroid) treatments, which reduce inflammation, are the primary treatment for macular edema caused by inflammatory eye diseases. These anti-inflammatory drugs are usually administered via eye drops, pills, or injections of sustained-release corticosteroids into or around the eye. Clinicians now have the option of three FDA-approved sustained-release corticosteroid implants for more serious or longer-lasting conditions:

- Ozurdex is an implant that delivers an extended release dose of dexamethasone. It is approved for DME, macular edema following retinal vein occlusion, and [non-infectious] uveitis.

- Retisert is an implant that delivers an extended release dose of fluocinolone acetonide. It is approved for the treatment of uveitis, as well as DME that doesn’t respond to corticosteroids.

- Iluvien is an implant that releases small doses of fluocinolone acetonide over the course of several years. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved it for treating DME.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), in the form of eye drops, are sometimes used either before or after cataract surgery to prevent the development of macular edema. Because they are chemically different from corticosteroids, NSAIDs may be used when the eye doesn’t respond to steroid treatment or to avoid the side-effects of steroid use in the eye.

Vitrectomy

Some cases of macular edema are caused when the vitreous (the gel that fills the area between the lens and the retina) pulls on the macula. Surgery to remove the vitreous gel, called a vitrectomy, relieves the pulling on the macula. Vitrectomy also may be required to remove blood that has collected in the vitreous or to correct vision when other treatments for macular edema are unsuccessful. Most vitrectomy surgeries are performed as outpatient surgery.